California’s agriculture regions are at a crossroads.

There is not enough water to maintain the state’s current agricultural water uses, while extreme heat, droughts, floods, air pollution, and economic instability affect farmers, communities, and the environment. Nature-based solutions offer a powerful approach to address these challenges by working with natural systems to increase climate resilience, create economic opportunities, improve water sustainability, and enhance public health.

Examples of nature-based solutions and their benefits include:

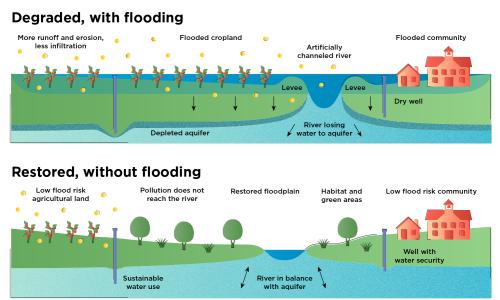

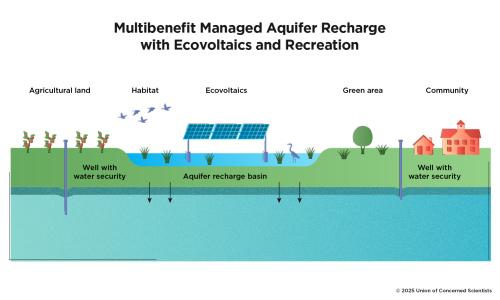

- Managed aquifer recharge: Captures flood water to replenish groundwater while creating habitat and reducing flood risk for communities

- Floodplain restoration: Reconnects rivers with natural floodplains to provide flood protection, groundwater recharge, and wildlife corridors

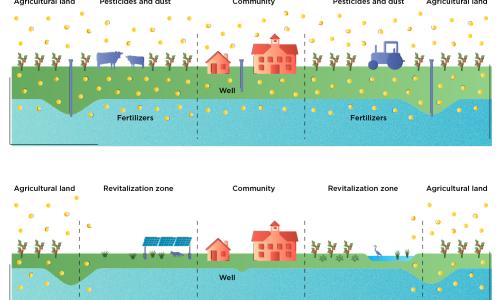

- Buffer zones around communities: Create pesticide-free areas that improve air quality and provide safe recreation spaces

- Constructed wetlands: Filters agricultural runoff and treats wastewater while creating habitat and educational opportunities

- Ecovoltaics: Combines solar energy with native habitat restoration, generating clean electricity while supporting pollinators and wildlife

In this guide, case studies of these solutions in action are presented along with frameworks for implementation.

Downloads

Citation

Fernandez-Bou, Angel S., Erin Woolley, Dezaraye Bagalayos, Sonia Sanchez, Stephanie Mercado, Jose Manuel Rodriguez-Flores, Anna Schiller, Gopal Penny, Molly Daniels. 2025. Working with Nature to Protect California's Agricultural Regions: How Nature-Based Solutions Can Build Resilience. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. https://doi.org/10.47923/2025.15967