Corporate consolidation—in which mergers and acquisitions of smaller

companies lead to fewer, larger companies—has been a trend for decades

in areas ranging from retail to technology. This consolidation gives

some corporations outsize power, a consequence President Biden addressed

in his 2021 executive order seeking to curb the “excessive concentration

of industry” (U.S. President 2021).

The food and agriculture sector is no exception to this troubling trend,

and the consequences can be far-reaching. For example, recent research

has shown that the nation's largest meat and poultry producer, Tyson

Foods (Statista 2022), has monopoly-like power that threatens the

health, safety, and well-being of chicken farmers, workers, and

communities in numerous ways (Boehm 2021a). Another recent study showed

how corporate consolidation in the US food system has increased food

prices and decreased food access (Howard and Hendrickson 2021).

In meat and poultry production, a key resource over which large

companies can exert control is the land used to grow crops for animal

feed. By affecting the supply chain both directly and indirectly

(through their influence on public policy, for example), large companies

can acquire a great deal of leverage over the way farmland is used and

managed. This control, in turn, can have significant consequences for

environmental and human health.

Congress, government agencies, and food companies can—and should—do more

to ensure that feed crops are grown sustainably and that competition in

the market is fair. Acting as the voice of the people, Congress makes

laws and provides oversight of government agencies that implement those

laws. Agencies such as the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) provide

support and technical assistance to farmers through various programs

that encourage sustainable farming practices. The USDA also enforces

laws intended to ensure fair competition in meat processing. The

Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission investigate

consolidation and enforce antitrust laws. Food companies like Tyson make

public sustainability commitments that are meant to guide their

businesses.

Below, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) provides an overview of

the extent of feed crop production in the United States and its impacts

on natural resources and the environment. We then use Tyson as a case

study to explore the substantial role large companies play in this

aspect of the food system. Specifically, we estimate the amount of

cropland needed to feed all the animals Tyson processes, which

demonstrates the magnitude and consequences of Tyson’s potential impact

on land use, crop farmers, and the environment. Finally, we offer

recommendations for the company and policymakers to make Tyson’s meat

and poultry production more sustainable and resilient.

Feed Crop Production and Its Impacts

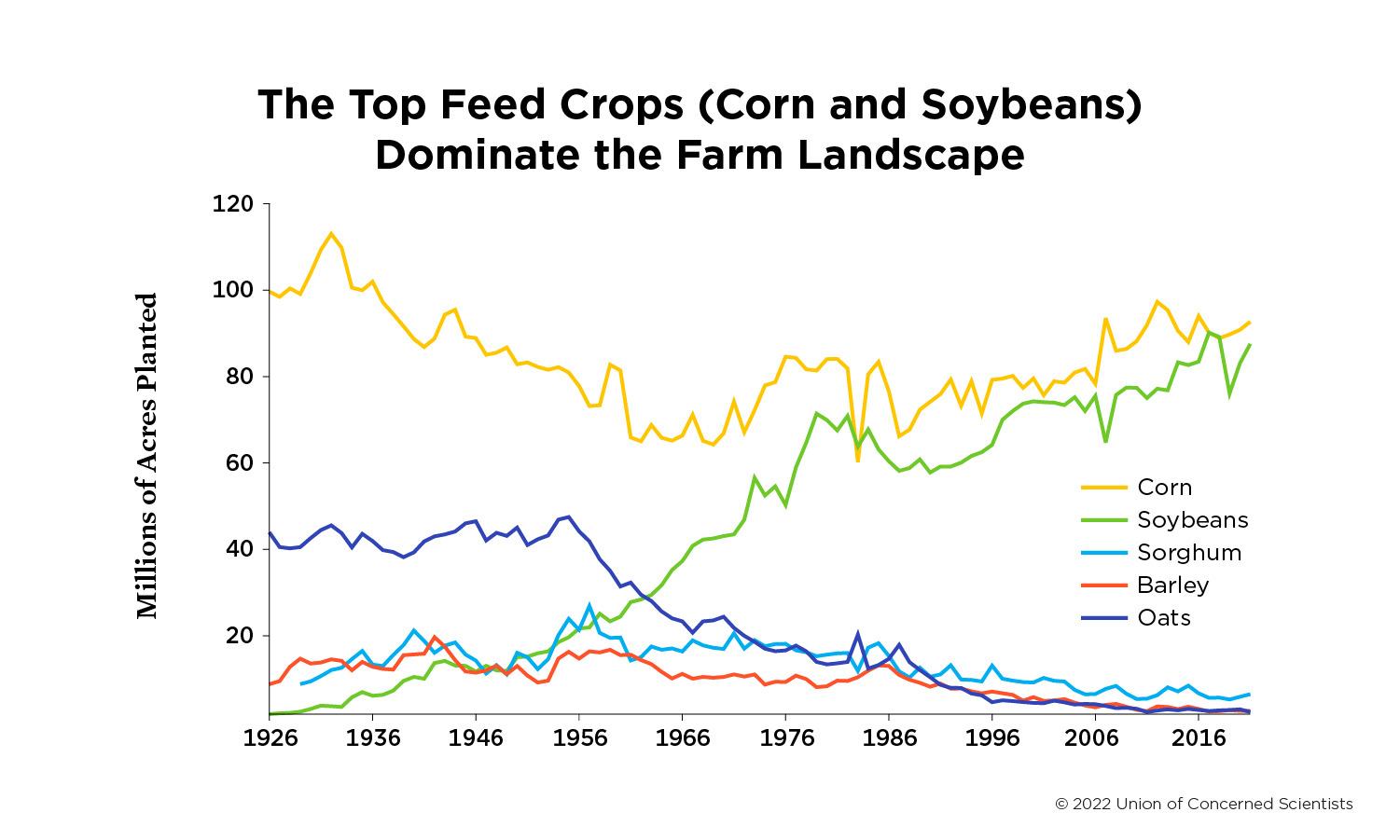

Animals raised for meat consume an enormous amount of feed each year,

and the crops predominantly used for this feed—corn and soybeans—take up

a proportionally large amount of land (Figure 1). Many livestock also

spend portions of their lives grazing (DeLonge 2016), but we do not

address the impact of that land use here.

out of 310 million total acres of US cropland, are the country’s biggest

crops. Much of it goes to produce animal feed for companies like Tyson

Foods.

In 2020, US farmers planted corn and soybeans on 174 million acres (NASS

2020)—an area that is larger than Texas and accounts for more than half

(56 percent) of the country’s 310 million total cropland acres. While

some of these crops are used for other purposes, such as biofuels and

processed foods, a large portion is used for animal feed (ERS 2021a).1

Land use on this scale has significant impacts, as described below.

Further, because land used for feed crop production could otherwise be

used to grow foods eaten by people (Cassidy et al. 2013), feed crop

production ultimately affects everyone.

The dominant way that major feed crops, particularly corn and soybeans,

are grown in the United States negatively affects the health of our

soil, water, air, and climate (Stillerman and DeLonge 2019). Feed crop

production also has an impact on the health and well-being of farmers

and communities that live near, or downstream from, the land where these

crops are grown. For example:

-

Erosion. Healthy soil is a vital life-support system at the very

foundation of our farms and food. However, every year, in part due

to unsustainable farming practices, US croplands lose more than

twice as much soil to erosion as the Great Plains are estimated to

have lost annually during the peak of the Dust Bowl (DeLonge and

Stillerman 2020). -

Climate vulnerability. As climate change impacts worsen, farms

are increasingly threatened by extreme weather. At the same time,

soil loss and degradation, in part due to management practices,

leave farms and surrounding communities even more vulnerable to

droughts and floods that cause billions of dollars in damage each

year (Basche 2017). -

Polluted drinking water. Clean drinking water is vital to

healthy communities, but excessive fertilizer and manure application

on croplands—particularly without safeguards to prevent

runoff—results in widespread contamination. In the heart of corn

country, Iowa is projected to spend up to $333 million over the next

five years to remove nitrates from drinking water (Boehm 2021b).

These costs will likely be borne disproportionately by small rural

communities. -

Dead zones. When nitrogen and other nutrients build up too much

in water, they can cause excessive growth of algae, which in turn

depletes oxygen and harms aquatic ecosystems. For example, nitrogen

fertilizer runoff from the Midwest, particularly from corn fields,

has caused up to $2.4 billion per year in damages to fisheries and

marine habitats in the Gulf of Mexico every year since 1980 (Boehm

2020). Damages also occur in streams, rivers, and lakes between the

farms and the Gulf, such as in Lake Erie (USGS 2016).

These agricultural and environmental challenges are driven by a number

of factors, including the dominant farming practices and the public

policies that shape them through incentives and other forms of support

(UCS n.d.). Large agricultural companies also wield considerable power

(GRAIN and IATP 2018), both by influencing policy (Feed the Truth and

MapLight 2021) and controlling many links in the supply chain (Facing

South 2021).

Further, the environmental impacts of cropland management can be

amplified by farmland consolidation. For decades, the land used to grow

crops has been consolidated into larger and fewer farms, a trend that is

undermining rural economies and communities in the Midwest and across

the nation (Ferguson 2021). Companies and government policies have also

played roles in this trend. Thus, when examining the impacts of feed

crop production on communities and the environment, it is critical to

consider the role of companies such as Tyson that buy and produce these

crops in large quantities.

Estimating Tyson’s Feed Crop Footprint

Tyson Foods is one of the largest food companies in the world and a

major corporation by any measure, ranking 73rd among the Fortune 500 in

2021 (Fortune 2021a). By the company’s own estimation, it produces 20

percent of all chicken, beef, and pork in the United States (Tyson Foods

2021a). To support this massive operation, Tyson buys large amounts of

raw materials including live cattle, live swine, corn, soybean meal, and

other feed ingredients, much of which it sells to contracted producers.

In 2018, it produced around 10 million metric tons of feed in a total of

32 feed mills throughout North America—enough to make Tyson the

ninth-largest feed producer in the world (Reus 2020)—and it has opened

more mills since then. In 2021, feed production represented 59 percent of the

company’s domestic poultry production costs (Tyson Foods 2021b).

While a previous UCS analysis demonstrated Tyson’s monopoly-like control

over chicken farmers and workers (Boehm 2021a), the degree to which it

has influence over other parts of the supply chain has been unclear. To

better understand the company’s influence over cropland, we estimated

how many corn and soybean acres are needed to produce feed grains for

the animals Tyson processes.

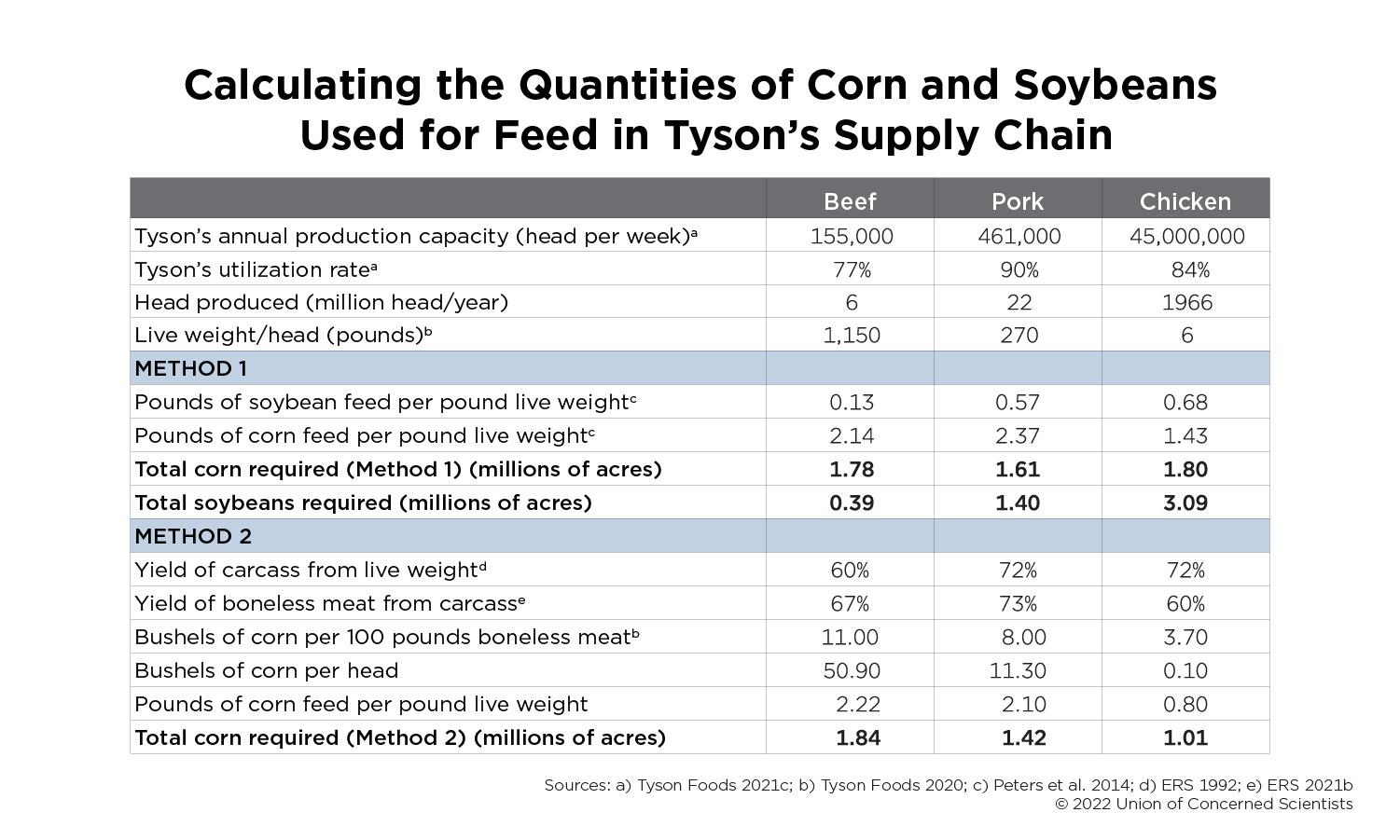

We first estimated how many animals are needed for all of Tyson’s beef,

pork, and chicken products each year. Based on Tyson’s reported weekly

production capacities and utilization rates, we estimated that the

company processed approximately 6 million head of cattle, 22 million

hogs, and nearly 2 billion chickens in 2020.2

We then estimated the amount of corn and soybeans used to feed all these

animals, based on a previous study (Peters et al. 2014). For these

calculations, we relied on data and conversion factors from both Tyson

Foods and the USDA’s Economic Research Service (Table 1). Specifically,

we used Tyson’s values for animal live weight per head, and ERS values

for yields of animal carcass from live weight (ERS 1992) and yields of

boneless meat per animal carcass (ERS 2021b).

with the total head of chicken, beef cattle, and hogs produced by Tyson

in 2020. We estimated the corn and soybeans needed by using conversion

factors from Peters et al. 2014 (available in the Supplemental Material;

Feed Conversions Summary Tab). We converted pounds of soybean and corn

to bushels using USDA standard conversion rates (56 pounds per bushel

for corn, 60 pounds per bushel for soybeans) (ERS 1992). We converted

bushels of crops to acres of crops by multiplying the most recently

published yields (172 bushels of corn per acre, 50.2 bushels of soybean

per acre) (NASS 2021). We compared the estimated amount of corn needed

as calculated above with the amount of corn needed as calculated using a

second method based on Tyson’s estimates for the bushels of corn

required per 100 pounds of boneless meat. In this case, we converted

total head produced to pounds of boneless meat using conversion factors

from the USDA. After converting to bushels of corn using Tyson’s

estimates, we estimated acres of corn by multiplying by the most

recently published corn yields.

Note: Beef harvest weight is the average of the range of 900 to 1,400

pounds. We assume a broiler-roaster chicken of between five to six

pounds. These estimates are similar to the national commercial averages

of live weight per head reported by the USDA NASS in 2020: 1,373 pounds

for beef, 289 pounds for pork, and six pounds for chicken.

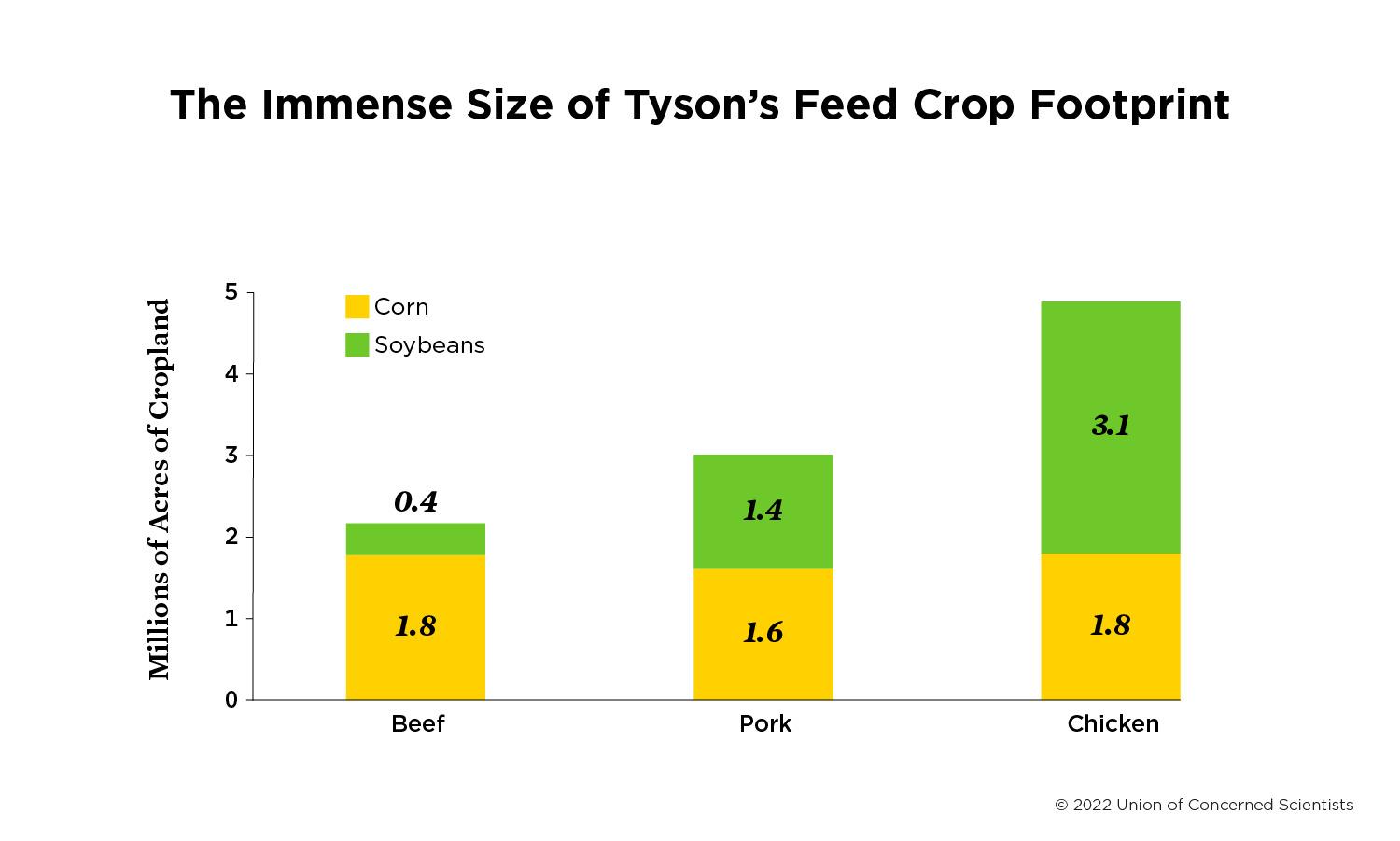

Finally, we estimated how many acres of land would be needed to grow

these feed crops. Based on our calculations, Tyson required between 4.3

million and 5.2 million acres of corn and 4.8 million acres of soybeans

in 2020 (Figure 2). That would make Tyson’s total feed crop footprint

between 9 million and 10 million acres—an area nearly twice the size of

New Jersey, and the equivalent of more than 5 percent of all US corn and

soybean acres planted in 2020.

single company’s demand for animal feed requires between 9 million and

10 million acres of corn and soybeans—an area nearly twice the size of

New Jersey, and the equivalent of more than 5 percent of all US corn and

soybean acres planted in 2020.

Tyson’s Track Record on Land Management

With so much land involved in its feed supply chain, Tyson could help

move US agriculture in a positive direction if it used its influence to

set high standards for the way farmers manage that land, and if it

provided support for farmers in meeting these standards. Setting and

supporting high standards would make Tyson a leader in protecting the

land, soil, and water resources on which its business success depends.

But it would also be good for the broader environment, the climate, and

the communities near and downstream from where the feed is grown. The

scale of Tyson’s operations provides the company with an opportunity to

help solve the problems that current US agricultural practices cause.

Spurring improvements to feed crop production would begin to make real

the company’s stated purpose “to raise the world’s expectations for how

much good food can do” (Tyson Foods 2021d) and could help meet its

recently announced goal of achieving net-zero heat-trapping emissions by

2050 (Quad-City Times 2021).

Back in 2018, Tyson acknowledged the relevance of feed cropland for the

company’s sustainability footprint, establishing a goal to “support

improved environmental practices” on 2 million corn acres by the end of

2020 (Tyson Foods 2018). However, as of 2021, Tyson had only enrolled

408,000 acres into pilot programs (Tyson Foods 2021d) and pushed its

target date out to 2025, in part because of COVID-19 (Polansek 2021).

The cropland footprint we estimated is more than five times the size of

Tyson’s self-defined sustainability goal, and around 23 times the size

of its progress to date. With hundreds of millions of dollars in profits

in recent years (Fortune 2021b), Tyson has the resources to accelerate

its commitment to improving production practices.

The gap between Tyson’s goal of 2 million acres and the total acreage on

which its business relies points to the larger problem of the outsize

influence large food and agriculture companies have on farmers and

farmland in general. The scope of Tyson’s supply chain, including the

cropland underpinning its operations, and its dominance in meat and

poultry processing (Boehm 2021a) represent a challenge for shifting

farming practices in a way that is good for both the environment and for

all farmers, particularly small and midsize farmers and those farmers

who are Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. For example,

farmers operating on tight margins may have trouble affording the

up-front costs of more sustainable practices, whether or not buyers like

Tyson want them to adopt those practices—unless those buyers are willing

to support the changes. Tyson’s current approach to working with farmers

on improved environmental practices, in partnership with Environmental

Defense Fund and Famers Business Network (Tyson Foods 2019), is a

positive step, but given the extent of its cropland footprint, Tyson has

the potential to make changes far beyond its current commitments and

progress. Moreover, doing so would be in line with the company’s

professed commitment to sustainability and transformational change

(Tyson Foods 2021e).

Solutions

Tyson’s power over farming practices on millions of acres of cropland,

and its environmental implications, is part of a problem that requires

multiple solutions. For one, Tyson and other food companies must help

drive more resilient and sustainable land management in supply chains.

Further, no single company should wield the leverage over food and farms

that Tyson does. This power creates significant barriers to transforming

the agricultural sector, as large food companies may thwart needed

changes by simply choosing not to support them.

Toward this end, Congress and the USDA should expand programs that

encourage farmers to adopt improved farming practices, and advance

policies to limit consolidation and increase competition in agriculture.

Here are our specific recommendations:

Tyson Foods should use its buying power and resources to help farmers

employ practices that conserve and build healthy soil.

-

Tyson and other food companies should follow through with, and

strengthen their existing commitments to, improving supply chain

management in ways that help farmers adopt healthy-soil farming

practices. Companies can do this by setting higher sustainability

standards for the feed in their supply chains and offering farmers

they purchase from incentives to meet those standards. -

Tyson should also advocate for state and federal healthy-soil

policies that accelerate or incentivize the production of

sustainably grown grains.

Congress and the USDA should do more to drive farmers' transition to

healthy-soil practices.

-

Congress should pass the Agricultural Resilience Act (S. 1337/H.R.

2803), which would dramatically expand investments in farm

conservation and research. Such investments would enable more

farmers to participate in proven, high-demand conservation programs

(e.g., the Conservation Stewardship Program, the Environmental

Quality Incentives Program) while advancing understanding of the

most effective practices and systems (through the Sustainable

Agriculture, Research, and Education program and the Agriculture and

Food Research Initiative). -

Congress can also increase the availability of technical assistance

through university-based extension programs. -

The USDA should strengthen existing conservation and research

programs and develop new programs and initiatives that advance

resilient and sustainable agriculture. It is critical, as UCS has

advised the department (UCS 2021), that USDA programs and

initiatives emphasize a holistic, systems approach that addresses

persistent and interdependent challenges including climate

adaptation and mitigation, racial equity, and sustainability.

Federal regulators and Congress should act to increase competition in

the meat industry.

-

The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission—which

have the legal authority to scrutinize and regulate antitrust

activity under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and the Clayton

Antitrust Act of 1914—should evaluate the degree of market power

that Tyson and other companies have acquired as a result of

concentration in meat and poultry supply chains. -

The USDA should act quickly on its stated intention (USDA 2021a) to

strengthen enforcement of the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921,

which was meant to ensure fair competition and curb abuses in the

meatpacking industry. This should include swift yet sound

promulgation and implementation of rules that will protect farmers,

nearby communities, and poultry plant workers from the impacts of

the highly concentrated livestock industry. -

The USDA should continue investments, begun in response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, to expand small- and medium-scale poultry

processing, giving farmers new market opportunities and helping to

curb the negative effects of consolidation among meatpackers (USDA

2021b). At the same time, Congress must include long-term support

for small- and medium-sized processors in the 2023 farm bill,

through provisions such as the Strengthening Local Processing Act of

2021 (S. 370/H.R. 1258) and the Agricultural Resilience Act.

Marcia DeLonge is the research director and senior scientist in the

UCS Food & Environment Program. Karen Perry Stillerman is the senior

strategist and senior analyst in the program.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible through the generous support of the

Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment and UCS

members.

The authors would like to thank four anonymous reviewers for their

thoughtful comments and contributions. At UCS, the authors thank

Charlotte Kirk Baer, Rebecca Boehm, Cynthia DeRocco, Samantha Eley, Rich

Hayes, Mike Lavender, Kyle Ann Sebastian, and Bryan Wadsworth for their

help in developing and refining this report. Finally, we’d like to thank

Brian Middleton for his editing work.

The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the

organization that funded the work or of the individuals who reviewed it.

The Union of Concerned Scientists bears sole responsibility for the

contents of this analysis.

Endnotes

-

According to the USDA, 46 percent of corn used in the United States

goes to a category described as “feed and residual use,” which is

the amount used domestically that is neither "food, alcohol, and

industrial use” nor “seed use.” -

We estimated Tyson’s total head of chicken, beef, and pork produced

by multiplying its reported weekly production capacities for each by

the reported utilization rates of its production facilities. Both

values were reported for fiscal year 2020 on Tyson’s website

(https://ir.tyson.com/about-tyson/facts/default.aspx).

References

Basche, Andrea. 2017. Turning Soils into Sponges: How Farmers Can Fight

Floods and Droughts. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/turning-soils-sponges

Boehm, Rebecca. 2020. Reviving the Dead Zone: Solutions to Benefit Both

Gulf Coast Fishers and Midwest Farmers. Cambridge, MA: Union of

Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/reviving-dead-zone

Boehm, Rebecca. 2021a. Tyson Spells Trouble for Arkansas: Its

Near-Monopoly on Chicken Threatens Farmers, Workers, and Communities.

Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/tyson-spells-trouble

Boehm, Rebecca. 2021b. Dirty Water, Degraded Soil: The Steep Costs of

Farm Pollution, and How Iowans Can Fix It Together. Cambridge, MA:

Union of Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/dirty-water-degraded-soil

Cassidy, Emily S., Paul C. West, James S. Gerber, and Jonathan A. Foley.

2013. “Redefining agricultural yields: from tonnes to people nourished

per hectare.” Environmental Research Letters 8(3): 4015.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034015/meta

DeLonge, Marcia. 2016. While BBQ season sizzles, a case for healthy

farms and better beef. The Equation (blog), July 14.

https://blog.ucsusa.org/marcia-delonge/while-bbq-season-sizzles-a-case-for-healthy-farms-and-better-beef/

DeLonge, Marcia, and Karen P. Stillerman. 2020. Eroding the Future: How

Soil Loss Threatens Farming and Our Food Supply. Cambridge, MA: Union

of Concerned Scientists. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/eroding-future

ERS (Economic Research Service). 1992. Weights, Measures, and

Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=41881

ERS (Economic Research Service). 2021a. Feedgrains sector at a glance.

https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/corn-and-other-feedgrains/feedgrains-sector-at-a-glance/

ERS (Economic Research Service). 2021b. Food availability (per capita)

data system.

https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/

Facing South. 2021. From the archives: Chicken empires.

https://www.facingsouth.org/2021/06/archives-chicken-empires

Feed the Truth and MapLight. 2021. Draining the Big Food Swamp.

Washington, DC: Feed the Truth.

https://feedthetruth.org/resources/the-political-clout-of-big-foods-trade-groups/

Ferguson, Rafter. 2021. Losing Ground: Farmland Consolidation and

Threats to New Farmers, Black Farmers, and the Future of Farming.

Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/losing-ground

Fortune. 2021a. Fortune 500.

https://fortune.com/fortune500/2021/search/

Fortune. 2021b. Fortune 500: Tyson Foods.

https://fortune.com/company/tyson-foods/fortune500/

GRAIN and IATP (Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy). 2018.

Emissions Impossible: How Big Meat and Dairy Are Heating Up the

Planet.

https://grain.org/article/entries/5976-emissions-impossible-how-big-meat-and-dairy-are-heating-up-the-planet

Howard, Philip H., and Mary Hendrickson. 2021. Corporate concentration

in the US food system makes food more expensive and less accessible for

many Americans. The Conversation (blog), February 8.

https://theconversation.com/corporate-concentration-in-the-us-food-system-makes-food-more-expensive-and-less-accessible-for-many-americans-151193

NASS (National Agricultural Statistics Service). 2020. Quick stats.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/

NASS (National Agricultural Statistics Service). 2021. Crop Production

2020 Summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/k3569432s/w3764081j/5712n018r/cropan21.pdf

Peters, Christian J., Jamie A. Picardy, Amelia Darrouzet-Nardi, and

Timothy S. Griffin. 2014. “Feed conversions, ration compositions, and

land use efficiencies of major livestock products in U.S. agricultural

systems.” Agricultural Systems 130: 35-43.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308521X14000778

Polansek, Tom. 2021. “Tyson Foods sets net-zero emissions goal, but

falls short on farming project.” Reuters, June 9.

https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/tyson-foods-sets-net-zero-emissions-goal-falls-short-farming-project-2021-06-09/

Quad-City Times. 2021. Biz Bytes: Tyson Foods Is Going Green.

https://qctimes.com/business/biz-bytes-tyson-foods-is-going-green/article_8ec5a8a3-7a58-511b-a993-f6691dd9ae1d.html

Reus, Ann. 2020. Tyson begins construction on Arkansas feed mill.

FeedStrategy (blog), May 11.

https://www.feedstrategy.com/animal-feed-manufacturers/tyson-begins-construction-on-arkansas-feed-mill/

Statista. 2022. Leading meat and poultry processing companies in the

United States in 2021, based on sales.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/264898/major-us-meat-and-poultry-companies-based-on-sales/

Stillerman, Karen P., and Marcia DeLonge. 2019. Safeguarding Soil: A

Smart Way to Protect Farmers, Taxpayers, and the Future of Our Food.

Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists.

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/safeguarding-soil

Tyson Foods. 2018. Sustaining Our World Together: 2018 Sustainability

Report.

https://www.tysonsustainability.com/downloads/Tyson_2018_Sustainability_Report.pdf

Tyson Foods. 2019. “Tyson Foods and EDF Launch Partnership to Accelerate

Sustainable Food Production.” Press release, January 15.

https://www.tysonfoods.com/news/news-releases/2019/1/tyson-foods-and-edf-launch-partnership-accelerate-sustainable-food

Tyson Foods. 2020. Investor Fact Book: Fiscal Year 2019.

https://s22.q4cdn.com/104708849/files/doc_factbook/2020/FactBookFY19_SinglePage-(Final).pdf

Tyson Foods. 2021a. Our story.

https://www.tysonfoods.com/who-we-are/our-story

Tyson Foods. 2021b. Form 10-K: Annual report pursuant to Section 13 or

15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, for the fiscal year ended

October 2, 2021.

https://ir.tyson.com/sec-filings/sec-filings-details/default.aspx?FilingId=15352500

Tyson Foods. 2021c. Tyson Foods Facts.

https://ir.tyson.com/about-tyson/facts/default.aspx

Tyson Foods. 2021d. The Formula to Feed the Future: 2020 Progress

Report.

https://www.tysonsustainability.com/downloads/Tyson_2020_Sustainability_Report.pdf

Tyson Foods. 2021e. Sustainability.

https://www.tysonfoods.com/sustainability

UCS (Union of Concerned Scientists). n.d. Sustainable agriculture: Food

production in the United States is at a crossroads.

https://www.ucsusa.org/food/sustainable-agriculture

UCS (Union of Concerned Scientists). 2021. Comment from Union of

Concerned Scientists re: Request for comment on the USDA Climate-Smart

Agriculture and Forestry Partnership Program.

https://www.regulations.gov/comment/USDA-2021-0010-0219

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2021a. “USDA to Begin Work to

Strengthen Enforcement of the Packers and Stockyards Act.” Press

release, June 11.

https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/06/11/usda-begin-work-strengthen-enforcement-packers-and-stockyards-act

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2021b. “USDA Announces $500

Million for Expanded Meat & Poultry Processing Capacity as Part of

Efforts to Increase Competition, Level the Playing Field for Family

Farmers and Ranchers, and Build a Better Food System.” Press release,

July 9.

https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/07/09/usda-announces-500-million-expanded-meat-poultry-processing

USGS (U.S. Geological Service). 2016. Nutrients and sediment in the

Western Lake Erie Basin.

https://www.usgs.gov/centers/ohio-kentucky-indiana-water-science-center/science/nutrients-and-sediment-western-lake-erie

U.S. President. Executive Order. “Promoting Competition in the American

Economy, Executive Order 14036 of July 9, 2021.” Federal Register Vol.

86, no. 132 (July 14, 2021): 36987-36999.

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/14/2021-15069/promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy